Sustainable Water

Back in Issue 25 in 2010 Graham Hepburn reviewed the importance of water and the sustainable process of harvesting drinking water from metal roofs. We republished a revised version of this in 2019. In light of the “Three Waters” reforms we feel this is again relevant, and now look at this topic again and update the content.

Rainwater Harvesting – of increasing potential value today

Eleven years after the original article and access to potable (and indeed any) water has become even more important in a world in which water supply is becoming a serious issue. Even in rain-rich New Zealand we are increasingly talking about control of water, water rationing, depletion of aquifers, and so on. At the same time we are increasingly suffering from downpours (mostly uncaptured) and flooding, as shown just recently in the South Island.

We are also looking at some limitations to supply of water for urban uses. As this is written, even during what seems like heavy rain, the Hunua Dams, on which Auckland relies heavily, have less than desirable levels of water, at 63% of full against a historical average of 87.5% for this time of year. This is still the case even two years after the drought and reasonable rain since.

Globally, although there is actually a finite non-reducing amount of water, which is not in fact being consumed, there appears in many places to be too little (or sometimes too much) of it for at least some of the time. There is little doubt that water is one of the planet’s most valuable commodities and maintaining water supply will become even more important as populations continue to increase, and increasing localised heat and dry spells can compromise local water supplies.

If the planet is going to be subjected to increasing extremes of flooding and drought, then security of good quality water supply will also be increasingly important. Let’s look at New Zealand specifically, although quite a lot of this is relevant to other countries.

Potable water

In rural areas with no mains supply there has been little choice but to harvest rainwater from roofs and collect it in tanks, and many rural households prefer this source, as it is cheaper and easier than digging a well or pumping stream/river water. In recent years suburban dwellers and even some water-using businesses have begun to get in on the act. We are now seeing, belatedly, some farmers or farming regions talking about building reservoirs to gather water when it rains for use when it doesn’t. Seems common sense and it apparently now happening – in the South Island.

Just harvesting rainwater for uses other than drinking drastically cuts demand on mains supply. It is estimated that in a typical dwelling only 5 litres per person per day is needed for cooking and drinking (potable water) while 150 litres per day is used for bathing, washing dishes and clothes, flushing toilets, in the garden or for washing down cars etc. (grey and black water). If this can be reduced by using rainwater for the non-potable purposes, a huge reduction in demand on the urban systems could result.

Of course there is a limit to how far this can go without affecting the economics of urban water supply and e.g. Watercare Services in Auckland prevent (or attempt to) collection of roof water for any purpose. In addition, the current Drinking Water Standards New Zealand (DWSNZ) do not allow the use of rainwater for potable uses where there is a potable supply available. (Of course this doesn’t affect non-potable use, which requires dual systems). Of course in some places the external supply has actually proven not to be of great quality (or complying with DWSNZ), and not everyone wants chlorinated water.

It seems that metering and charging for water use is commercially important in today’s world where everything has its price. Apparently, at least in Auckland, the metered amount of supplied water is also used to determine the volume of and charges for waste-water treatment. Measurement of wastewater is significantly more difficult than just metering all water in. So use of rainwater from the roof would not allow this cost to be fully recharged, and since both water supply and wastewater treatment are a business operation this would be unacceptable without a revenue re-structure for these services.

The trend to water collection is partly due to greater environmental awareness but also to the fact that water is becoming an increasingly expensive commodity. The charges for water in urban areas steadily increase year on year. Some Councils have also been encouraging home owners and businesses – sometimes with financial incentives - to collect rainwater for non-potable purposes because this has twin advantages: it helps to reduce stormwater flows, and alleviates some of the pressure on water supply and water infrastructure from a growing population.

Now we have the proposed Three Waters Reform Programme, essentially a central government water regulator/supplier.

From the website https://threewaters.govt.nz/

“The Three Waters Reform Programme is a major, intergenerational project. It aims to ensure that New Zealand’s three waters—our drinking water, wastewater and stormwater—infrastructure and services are planned, maintained and delivered so that these networks are affordable and fit for purpose. The current situation does not achieve this for all communities.

Today, on behalf of their communities, 67 different councils own and operate the majority of the drinking water, wastewater and stormwater services across Aotearoa.

Working with councils, the Government proposes to establish four new publicly-owned multi-regional entities that benefit from scale and operational efficiencies and reflect neighbouring catchments and communities of interest. Central to this plan is our ongoing partnership with the local government sector and mana whenua”

In New Zealand currently, i.e. prior to the proposed water reforms, each local authority has the responsibility for funding all water and waste infrastructure. This has become increasingly difficult with tightening regulatory environments both on potable water standards and wastewater discharges. If the true cost of maintaining infrastructure were levied on ratepayers, councillors would lose elections. Therefore, over decades, the investment in water and wastewater infrastructure has been less than necessary in regional New Zealand (and some urban areas). This is a key factor in the proposed water reforms. Essentially one purpose of the reforms is to invest in infrastructure as required for both water and wastewater on an “area” basis, for example, essentially the whole South Island is proposed to be one entity. All those residing in that area would fund the whole area, meaning those with efficient systems due to population density (e.g. Christchurch – although how good is their system post-earthquake?) will pay more and those in say Tekapo will pay less than their own true local cost. As seen by the “protesting” local authorities, this is not palatable for all.

As we have not invested in adequate new infrastructure, one good way to limit cost would seem to be to limit demand, and rainwater harvesting is a cost effective mechanism to achieve this.

In spite of resistance to the proposed programme already being raised across NZ, it seems likely to result in at least some changes. This may or may not allow for a wider use of rainwater for potable use (probably with design requirements to be met – e.g. roof type and storage tank materials). The cost of safe quality water provision for small communities in rural New Zealand without funding change would become cost-prohibitive. Without change providing for either central government funding or area-wide rate base funding, many small communities will be unable to afford to comply with DWSNZ. Therefore, we can’t help but think that changes in the DWSNZ allowing for rainwater to be used as a potable source in smaller communities should be an option.

What we rural dwellers already know is that it is quite possible to collect and store all the water needed (normally), and to process grey and black water onsite – often at a lower cost than fully provided urban services in semi-rural areas.

Although drinking water is the smallest component of water used, currently all water must be to the DWSNZ and this means the roof must provide clean uncontaminated water. The best roofing material for minimisation of the risks of contaminants is long run metal roofing, painted or unpainted.

Reducing demand

Collection and storage of water also helps to conserve this valuable resource and will reduce the need for councils to build more dams or find other water sources. If you are providing and treating your own water, then that also cuts demands on treatment facilities and pumping stations, which in turn means they will need to consume less energy. The individual owner of the storage therefore also uses less water and for those in metered connections this will reduce their water cost.

As New Zealanders have known for decades, catching water off a metal roof for drinking and other household uses is cheap, easy and safe as long as some basic precautions are taken.

Safety of roof water

BRANZ says metal roofs are safe from which to collect rainwater, but a check should be made to ensure there is no lead, chromium or cadmium in the roof and its flashings or in any soldering or paint. Paints used by NZ coil-coaters have been demonstrated to produce no harmful runoff.

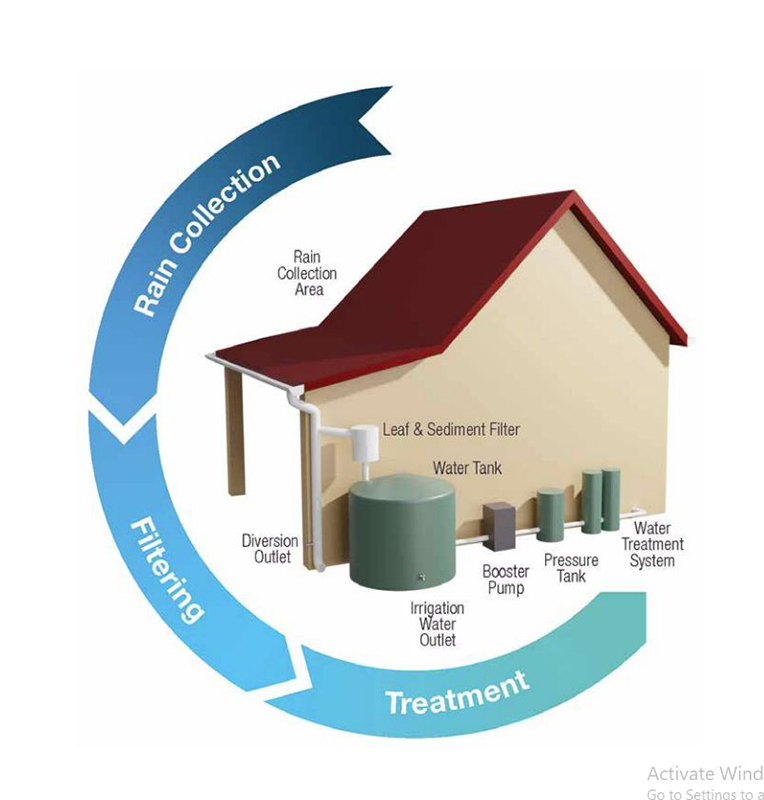

The roof and gutters need to be cleaned regularly with diverters in place to make sure contaminants such as bird droppings that are being washed away during cleaning aren’t entering the water supply. And a first-flush diverter and debris diverters should be installed – this reduces the risk of contaminants entering the storage. Treating roof water to potable level can be as simple as coarse filtering incoming flow and finer filtering and UV treatment before pumping to the house. (see the illustration). The best roofing material to limit contaminants is long run metal.

Manufacture

Pacific Coil Coaters and New Zealand Steel have tested their painting systems for the potential to release contaminants and have shown that there are no contaminants released of any public health concern. Therefore, excluding other environmental factors, when you use COLORSTEEL® or ColorCote® pre-painted metal roofs for the harvesting of rainwater, you can rest assured that the product you are using will not contaminate the water. Zincalume ® is also good. This is not necessarily true of product not painted in NZ.

Roll-forming of metal for roofing uses no water and the manufacture of the steel coil from which metal roofing is made uses minimal water. As an example, although New Zealand Steel’s plant at Glenbrook uses about 1 million tonnes of water a day in the steel making process, this is constantly recycled – cleaned, cooled and recirculated - so that only 1% of it is discharged and what is discharged is clean enough to drink.

Stormwater and Flooding mitigation

In urban environments with their proliferation of impermeable surfaces, stormwater during heavy downpours can and does cause surface flooding and overwhelms sewers (where there is cross-connection between stormwater drains and sewers, as there still is in Auckland, this is worse and more frequent), causing foul-water discharge into waterways.

As climate change continues we will see increasingly irregular but heavy rain falls which will exacerbate this problem.

Collecting water off roofs reduces stormwater problems by attenuating the flood peak, helps to conserve a valuable resource, and will reduce the need for councils to build more dams or find other water sources. If you are providing your own water, then that also cuts demands on treatment facilities and pumping stations, which in turn means they will need to consume less energy.

In Australian cities all new properties have been required for some years to provide short-term on-site water storage, not to provide drinking water but to prevent overwhelming the stormwater drainage systems. Something we should be looking at in New Zealand? Such urban collected water, while not reducing the need for potable water (and its revenue stream) can also be used for greywater and garden watering.

Sustainability

After the NZ Green Building Council (NZGBC) introduced the Green Star building rating system for commercial and industrial buildings in the 2000s, which does include credit for water processing, it was realised that there is also a need to encourage sustainable homes, and there are schemes for such less complex buildings elsewhere in the world. NZGBC has developed the Homestar system to fill this gap.

After several revisions, in 2021 Homestar Version 5 has been issued. This provides credits for using metal roofing to gather rainwater for much the same reasons as listed above.

Credits particularly relevant to water collection are :-

EF3 - To encourage and recognize water conservation through water efficient fittings and rainwater harvesting.

EN3 - Encourage and recognize specification and use of responsibly sourced materials that have lower environmental impacts over their lifetime.

EN5 - Site water and ecology - to encourage whole of site approach that improves the ecological value of the site while reducing stormwater runoff flooding pollution and erosion.

And while not related exclusively to rainwater processing, points for metal roofing can also be gained for EN4 - Construction waste - to encourage and recognize effective strategies that reduce the environmental impact of construction waste.

Overall

Homeowners collecting drinking water and greywater replacement from metal roofs can do so knowing they are risklessly harvesting a renewable resource which can also help with urban supply and stormwater flooding mitigation. Metal is the roofing material that is the best suited material for rainwater collection, and this is recognised by the NZGBC Homestar rating system.