Sustainable and Potable Water

Sustainable and Potable Water

We have earlier published a couple of articles about metal roofing and the collection and processing of sustainable and potable water. Back in Issue 25 in 2010 Graham Hepburn reviewed the importance of water and the sustainable process of harvesting drinking water from metal roofs. We republished a revised version of this in 2021 in light of the then proposed “Three Waters” reforms (now abandoned).

The publication by the Water Services Authority (Taumata Arowai) of a new Acceptable Solution for Roof Water Supplies which came into force on 14th November 2022 prompted a fresh look at this topic. As usual following this AS implies compliance with the Standards.

These newly published documents suggest that this is again relevant, and we will now look at this topic again.

Rainwater Harvesting – of increasingly potential value today

Fifteen years after the original article access to potable (and indeed any) water has become even more important in a world in which water supply is becoming a serious issue. Even in rain-rich New Zealand we are increasingly talking about control of water, water rationing, depletion of aquifers, and so on. At the same time we are increasingly suffering from downpours (mostly uncaptured) and flooding, as shown in the Hawkes Bay catastrophe of 2023.

We are also looking at some limitations to supply of water for urban uses. As this is written, even during what has been heavy rain in 2024, the Auckland system, on which Auckland relies, have less than desirable levels of water at 63% of full against a historical average of 79% for this time of year (14% down). Individual Auckland Dams are between 10 and 30% down on previous average.

Storage trends are down consistently – published by Watercare Services.

There is actually a finite non-reducing amount of water (i.e. total water on the Earth) which is not in fact being consumed in the sense of disappearing. Depending on which source you use, only 3% of the 1.4 billion km³ water is fresh and of this ⅔, or 2%, is unavailable (locked up in icebergs or underground). This leaves a mere 14 million km³. But of this "only" 13,000 km³ is in the atmosphere to become rain.

And, there appears in many places to be too little (or sometimes too much) of this water for at least some of the time. There is little doubt that water is one of the planet’s most valuable commodities and maintaining water supply will become even more important as populations continue to increase, and increasing localised heat and dry spells can compromise local water supplies.

If the planet is going to be subjected to increasing extremes of flooding and drought, then security of good quality water supply will also be increasingly important. Let’s look at New Zealand specifically, although quite a lot of this is relevant to other countries.

Potable water

In rural areas with no mains supply the easiest source is to harvest rainwater from roofs and collect it in tanks, treated or untreated and then pump round the system, and many rural households prefer this source, as cheaper and easier than digging a well or pumping stream/river water. This does depend on a suitable roofing material to gather clean rainwater.

Just harvesting rainwater for uses other than drinking drastically cuts demand on mains supply. It is estimated that only 5 litres per person per day is needed for cooking and drinking (potable) while 150 litres per day is used for bathing, washing dishes and clothes, in the garden or for washing down cars etc, and for flushing toilets, what is termed respectively grey and black water. If this demand can be reduced by using rainwater for non-potable purposes, a huge reduction in demand on the urban systems could result.

Of course there is a limit to how far this can go without affecting the economics of urban water supply and e.g. Watercare Services in Auckland prevent (or attempt to) collection of roof water for any purpose. In addition, the current Drinking Water Standards New Zealand (DWSNZ) do not allow the use of rainwater for potable uses where there is a potable mains supply available. (Of course this doesn’t affect non-potable use, which does require dual systems).

It seems that metering and charging for water use is demand management, important in today’s world where everything has its price. The metered amount of supplied water is usually used to determine the charges for waste-water treatment, as well as for the incoming mains water.

The traditional cost of treating water and the corresponding waste water treatment when done well is approx. USD$6/m³ (NZ$12/m³). In NZ, we charge on average less than 10% of the true cost.

Recent NZ Legislation is making it simpler for small rural communities/campsites and the like to comply with NZDWS (the drinking water standards) with the introduction of an Acceptable Solution for Roof Water Drinking Supplies.

The trend to water collection is partly due to greater environmental awareness but also to the fact that charges for water increase year on year. Some Councils have also been encouraging home owners and businesses – sometimes with financial incentives - to collect rainwater for non-potable purposes because this has twin advantages: it helps to reduce stormwater flows into the system by holding it on site, and it alleviates some of the pressure on water supply and water infrastructure from a growing population.

The Acceptable Solution referred to deals with how to use roof gathered water for one or several buildings serving numbers of people (i.e. not restricted to single dwellings). If the collection serves more than one dwelling, it must then comply with the standards. The AS allows this without the undue compliance costs that normally come with a water supply authority provision.

In New Zealand, each local authority has the responsibility for funding all water and waste infrastructure. This has become increasingly difficult with tightening regulatory environments both on potable water standards and wastewater discharges. If the true cost of maintaining infrastructure were levied on ratepayers, councillors would lose elections. Therefore, over decades, the investment in water and wastewater infrastructure has been way less than necessary in regional New Zealand (and some urban areas).

As we have not invested in adequate new infrastructure, one good way to limit cost is to limit demand, and rainwater harvesting is a cost effective mechanism to achieve this.

The new Acceptable Solution provides for wider use of rainwater for potable and non-potable storage and provides design requirements to be met – e.g. , processing and storage tank materials, The cost of safe quality water provision for small communities in rural New Zealand without funding change is becoming cost-prohibitive. Certainly without change providing for either central government funding or area-wide rate base funding, many small communities will be unable to afford to comply with DWSNZ. Therefore, we can’t help but think that changes in the DWSNZ allowing for rainwater to be used as a potable source in smaller communities should be an option.

What we rural dwellers already know is that it is quite possible to collect and store all the water needed for living (normally), and to process grey and black water onsite – often at a lower cost than fully provided urban services in semi-rural areas.

It is actually environmentally neutral – all the rainwater that falls on the building is returned to the ground in some way (depending on waste water processing method).

Although drinking water is the smallest component of water used, currently all water must be to the DWSNZ and this means the roof must provide clean uncontaminated water. The best roofing material for minimisation of the risks of contaminants is long run metal roofing, painted or unpainted. Key aspects of the AS, that concludes long-run metal coated roofing is the best option for roof material, include that the following contaminants must be monitored and be within the limits:

- Benzo[a]pyrene < 50% MAV = 0.35ppb

- Cadmium < 50%MAV = 2ppb

- Copper < 50%MAV = 1ppm

- Lead < 50%MAV = 5ppb

- Zinc < 50%MAV = 750ppb

Long Run metal roofing meets these requirements easily and reduces the propensity for lichen and the like to form in unwashed areas of the roof.

Reducing demand

Collection and storage of water also helps to conserve this valuable resource and will reduce the need for councils to build more dams or find other water sources. If you are providing your own water, then that also cuts demands on treatment facilities and pumping stations, which in turn means they will need to consume less energy. The individual owner of the storage therefore also uses less water and for those in metered connections will reduce their water cost.

As New Zealanders have known for decades, catching water off a metal roof for drinking and other household uses is cheap, easy and safe as long as some basic precautions are taken.

Safety of roof water

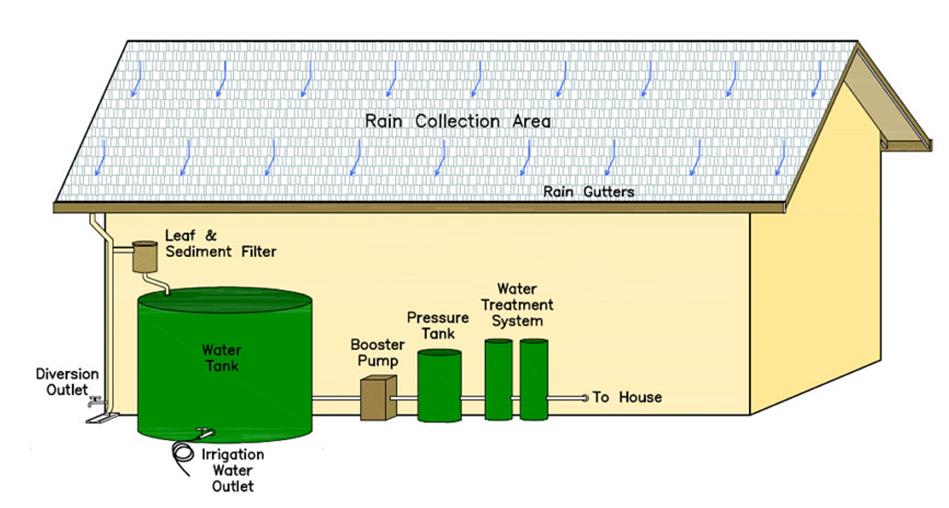

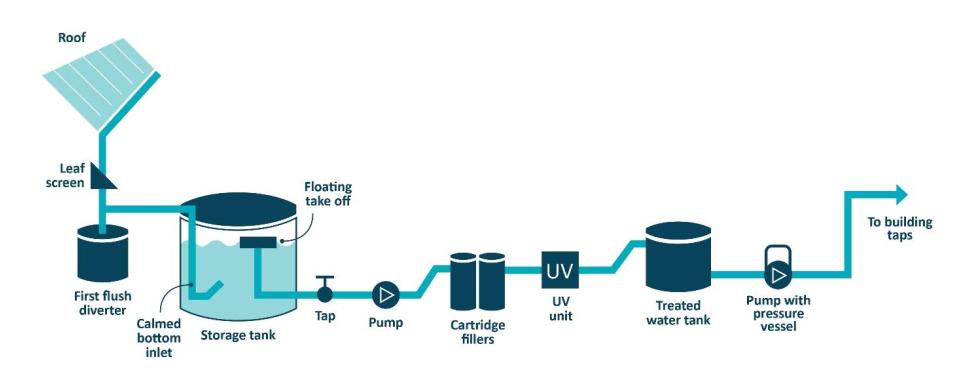

The roof and gutters do need to be cleaned regularly with diverters in place to make sure contaminants such as bird droppings that are being washed away aren’t entering the water supply. Treating roof water to potable level can be as simple as coarse filtering incoming flow and finer filtering and UV treatment before pumping to the house. (see the illustration). The Acceptable Solution and the Drinking Water Quality Assurance rules 2022 provide extensive information on cleaning roof collected water. Complying with the AS will provide clean water.

Stormwater and Flooding mitigation

In urban environments with their proliferation of impermeable surfaces, stormwater during heavy downpours can and does cause surface flooding and overwhelm sewers (where there is cross-connection between stormwater drains and sewers, as there still is in Auckland, this is worse and more frequent), causing foul-water discharge into waterways.

As climate change continues we will see increasingly irregular but heavy rain falls which will exacerbate this problem.

Collecting water off roofs reduces stormwater problems by attenuating the flood peak, helps to conserve a valuable resource, and will reduce the need for councils to build more dams or find other water sources. If you are providing your own water, then that also cuts demands on treatment facilities and pumping stations, which in turn means they will need to consume less energy.

Sustainability

After several revisions, in 2022 Homestar Version 5 was issued by the NZ Green Building Council. This provides credits for using metal roofing to gather rainwater for much the same reasons as listed above.

Credits particularly relevant to water collection are :

- EF3 - To encourage and recognize water conservation through water efficient fittings and rainwater harvesting.

- EN3 - Encourage and recognize specification and use of responsibly sourced materials that have lower environmental impacts over their lifetime.

- EN5 - Site water and ecology - to encourage whole of site approach that improves the ecological value of the site while reducing stormwater runoff flooding pollution and erosion.

And while not related exclusively to rainwater processing, points for metal roofing can also be gained for EN4 - Construction waste - to encourage and recognize effective strategies that reduce the environmental impact of construction waste.

Overall

Homeowners collecting drinking water and greywater replacement from metal roofs can do so knowing they are risklessly harvesting a renewable resource which can also help with urban supply and stormwater flooding mitigation. Metal is the roofing material that is the best suited material for rainwater collection, and this is recognised by the NZGBC Homestar rating system, and by the Acceptable Solution.

Typical basic rainwater collections system.

From the draft Acceptable Solution. Note separate tank for treated water.